A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A VOLUNTEER ELE-CARETAKER

A Guest Blog by Barbara Garrett

In the Summer of 2013, I followed my bliss to South Africa where I worked at the Knysna Elephant Park. Kynsna is a tourist attraction on the Garden Route in the Western Cape.  I volunteered for AERU, the African Elephant Research Unit. AERU has been onsite at the Park since 2009, and is studying the behavior and welfare of elephants in a captive environment. (More information about the research HERE) Apart from starting my life over again and being born Cynthia Moss or Joyce Pool or Dame Daphne Sheldrick, this was the closest I was ever going to get to doing the thing I’ve always wanted to do: study elephants.

I volunteered for AERU, the African Elephant Research Unit. AERU has been onsite at the Park since 2009, and is studying the behavior and welfare of elephants in a captive environment. (More information about the research HERE) Apart from starting my life over again and being born Cynthia Moss or Joyce Pool or Dame Daphne Sheldrick, this was the closest I was ever going to get to doing the thing I’ve always wanted to do: study elephants.

The first few days at the park are still a blur. On top of mind-numbing jet lag, having traveled some 30 total hours, it reminded me of boot camp (even though I’ve never been to boot camp, this had to be it), and there was an overwhelming amount of information to absorb in very short order about not only the extensive daily operations and rules required to run the Park, but also about the elephants themselves.

It was hard, physically challenging work at times - mucking stalls, dragging branches, hauling heaping wheelbarrows full of soiled sawdust up the famed “dung mountain,” over and over and over again. As a 52 year-old lifelong desk job worker, manual labor is fairly foreign to me.Fortunately I am in good physical condition so while the work was hard, I hung in there with the rest of the mostly 20-something year-old volunteers. It was actually quite energizing to start the day off with some old fashioned hard work!

DETAILS ABOUT THE DAY

The work in the field was not so much physically challenging, although we did sometimes have to walk long distances as we followed the elephants around their 60-hectare (about 150 acres) enclosure, as it was mentally challenging. Recording the behavior of seven indistinguishable (initially) elephants, or calculating the distance between a single elephant in relation to all of the others at 5-minute intervals seemed at first like the hardest thing I’ve ever had to learn. Elephants are unique and they all have individual physical characteristics and distinct personalities, and we had to know who was who out in the field - massive Sally, the patient and formidable one-tusked matriarch; Nandi, the second-in-command and largest female and her daughter, Thandi, with the Dumbo-like ears that billowed up like a sail anytime the wind hit them the right way, which always made her look like she was about to charge!; tiny nugget Thato, with the funny little tail, itsy, bitsy tusks and frilly, girly ears; sweet, independent Keisha, ears tattered and torn, battle wounds she earned in translocation as a scared, lonely, and starving days-old calf; Mashudu and Shungu, the adolescent boys, always play-fighting but each gentle and sweet in their own ways; and the teenaged bulls, Clyde and Shaka. (Read the backgrounds of these elephants HERE)

There is a whole bunch of work that has to be done every day and as a volunteer I could be (and was) assigned to any number of tasks on any given day. Each day started before dawn and ended after dusk and included several hours of collecting data in the field. But there was also Bana grass (or “elephant grass”) to be planted or cut and hauled into the boma (the elephant’s enclosure); fruit to be chopped; food buckets to be cleaned, sterilized and filled; tree branches (or “browse”) dragged in every night for the elephants to feed on throughout the night; and every night there was a round of research to be done up in the boma loft after the elephants were put to bed. The quiet evenings in the boma were very special (even the late, late shift – an hour in the middle of the night) - there is absolutely nothing quite like the sound of elephants snoring, farting, and rumbling to each other that will endear them to you for the rest of your life.

But when I wasn’t working, I got to do the thing I went there to do the most: I went out into the field to just be with the elephants. Following them up and down and around in the field, watching them as they foraged, interacted with the public and each other, wallowing in mud holes and playing was endlessly entertaining and interesting. And if I was lucky and they stood in one place long enough, I got to touch them, feed them fruit, and caress them – patting them gently on the side or stroking the soft, tender skin behind their ears, kiss them on the trunk, look them in the eyes, and whisper to them how much they were loved by me and so many others like me.

KNYSNA CONFLICT

As an elephant advocate in the U.S., I admit that I had moral and ethical conflicts about going to work at a facility where elephants are kept in captivity and are subjected to a constant barrage of tourists, day in and day out. And since I returned and shared my experience with others, I have received some hate mail for daring to call myself an advocate whilst supporting an elephant tourist attraction. I am against circus elephants and elephants in captivity in general – but like anything else, there are gray areas. Some zoos are better than others, by far; the same goes with circuses. Whereas I used to be completely anti-zoo and anti-circus and anti-captivity about every, living creature, I decided I needed to conserve my energy and choose my particular battle because all of the world’s animals are never going to be 100% free. So today, for the most part, I no longer advocate against elephants in captivity or in circuses. It’s not that I don’t care. I just choose to focus my attention on elephants being poached, something that is much worse by far than keeping an elephant in captivity in a place such as Knysna.

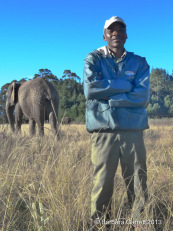

My final analysis is that the elephants at the Knysna Elephant Park, many of whom came from truly horrible situations, are deeply loved, have the best possible care, and, most importantly, are safe from harm. The people who work at Knysna are committed and dedicated to their elephants. Most of the guides have worked there for years, having traveled great distances from their homes and families to live and work there. I became friends with the guides, the other volunteers, and the AERU staff. Everything about the place was transparent and all of my questions were answered. Are the elephants captive? Yes. Do the guides carry bullhooks? Yes. Are the elephants used for tourist rides? Yes. Nonetheless, at no point did I ever feel like this was a horrible environment in which elephants should be kept. I did not see any stereotypic behaviors. I did not see anyone abuse the elephants with bullhooks. There are tourist rides but only first thing in the morning when the elephants leave the boma and get taken out to the field. If I can anthropomorphize, the elephants there are content, and God knows they are better off than the environments from which they came.

While this experience is not for everyone – just getting there isn’t for the faint of heart – it was the single most exciting and interesting thing I’ve ever done, an experience that affected me on every level. Not a day goes by that I don’t think about “my babies” and my time there. I will definitely go back, and when I do, I fully expect my special elephants – Mashudu, Thato, and Keisha – to remember me.

Barbara Garrett, January, 2014